There are few operas which, at once, give some insight into the history of the current UK opera scene, the sexual politics of the 1940s and the darkness within Benjamin Britten’s mind. Peter Grimes does all that and also provides a visceral and heart-rending story, deep in meaning, high in emotion.

The opera starts with an interrogation of the eponymous fisherman after the passing of his young apprentice at sea. Grimes claims the lad died of thirst; the local “Borough” folk suspect a much murkier end. The court settles on a verdict of “accidental death” but neither the accused nor the villagers will let the matter be. Soon after, Grimes asks his friend to find another boy for him to take to sea, a move which presages a tragic ending.

Peter Grimes was a major success when it opened soon after the Second World War. It was the first work put on by the Sadler’s Wells opera company at their Rosebery Avenue home; it was also the last one they put on before moving into their present London Coliseum venue, where they later changed their name to the English National Opera.

Britten’s partner Peter Pears took on the leading role on both occasions opposite the artistic director Joan Cross. While being critically and publicly acclaimed, some in the company cried favouritism while others saw an agenda close to Britten’s heart, calling it “a powerful allegory of homosexual oppression”. Its success led to transfers across the pond (led by Leonard Bernstein) and across town at the Royal Opera House, where Pears and Cross reprised their roles.

Britten, reacting to homophobic reactions within the company to Peter Grimes, left Sadler’s Wells to begin what is now known as the Aldeburgh Festival of Music and Arts. The world-famous event returns to its Suffolk home after three years away this summer for its 73rd outing.

Back to the present. Director Deborah Warner is no stranger to Britten – her pre-Covid Billy Budd was described as “truly extraordinary” by one critic – and this Grimes is another strong production. Bernstein once said of Britten that “if you hear it, not just listen to it superficially, you become aware of something very dark”, and she certainly brings that out in this work both in a visual and an atmospheric sense.

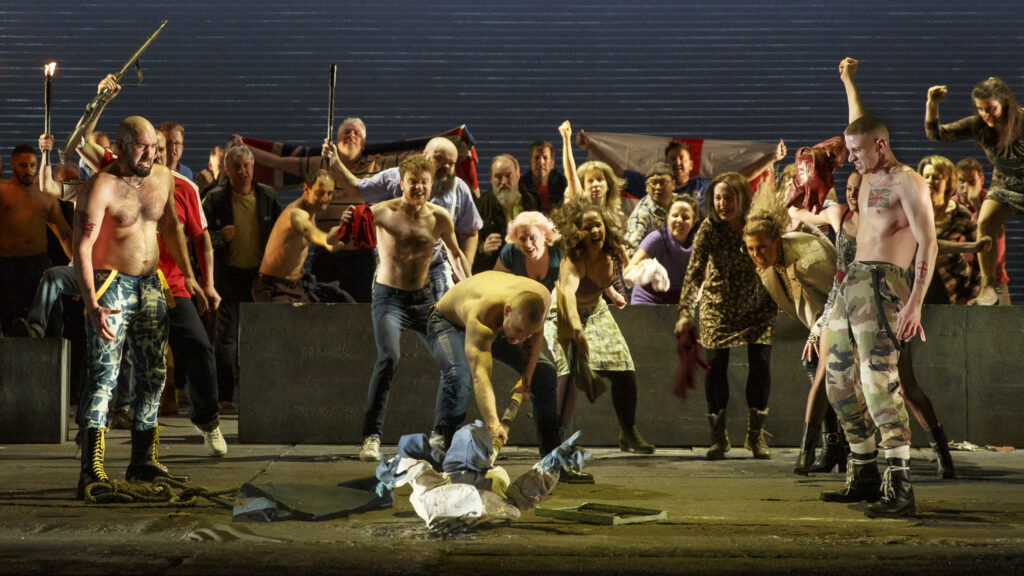

Warner draws upon an immense chorus and a chiaroscuro palette from the off: Grimes’s questioning is carried out on a barely lit stage while a silhouetted crowd wave torches over their heads as if they were at a Coldplay gig. She adopts the same approach at an emotional level, highlighting both the individual acts of kindness and the lynch mob mentality within the Borough.

The ever-present sea is portrayed as steel-grey backdrop, an unremitting reminder of the fate that awaits Grimes and those who sail with him. It also serves as the wellspring of Grimes’s Trumpian confidence: he feels that as long he brings in the big catches, the fish and the money he makes from them will earn him forgiveness, acceptance and respect from his peers.

Unlike with Budd, Warner has to contend with female characters. Neither Britten nor his librettist Montagu Slater do themselves proud with the underwritten women here, with the sole exception of Ellen Orford (played by Swedish soprano Maria Bengtsson). There’s a heartfelt defiance in her voice as she tells the baying mob “Let her among you without fault / Cast the first stone” and her staunch defence of Grimes is beautifully brought out through both singing and acting.

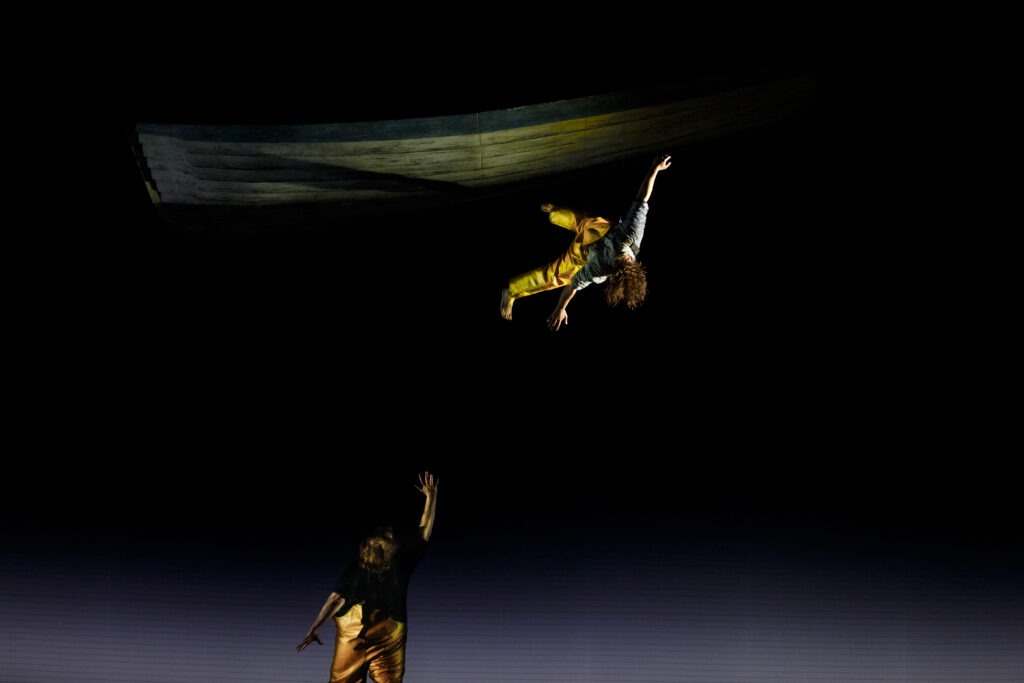

In the title role, Allan Clayton imbues the ursine fisherman with a terrific blend of regret and anger, railing against the poor hands dealt to him by fate. Tormented by the sight of his dead helper – shown as a ghostly form twisting in the air above Grimes’s head which only he can see – the slow but definite descent into tortured madness is thrillingly executed and his final actions are a true hammer to the heart.

Elsewhere, Bryn Terfel makes a welcome return to the London stage as Captain Balstrode, Grimes’s sole friend in the Borough. Terfel first sung the part 24 years ago at the same venue and he displays an immense understanding of and connection to this key role. Apothecary Ned Keene (Jacques Imbrailo) is portrayed by Warner as a local wheeler-dealer in tracksuit and bumbag; while this fits in somewhat with his characters as a supplier of drugs to the community, it tonally jars with the more workmanlike outfits around him.

Peter Grimes is not what one would call an enjoyable experience. It is a gut-churning journey with little in the way of levity, there are few likeable characters and a foreboding atmosphere is present throughout. Warner has done well not to hold back on the pitch-black core of the work (which would be understandable in these gloomy times) and this Grimes certainly doesn’t pull its punches.

Peter Grimes continues at the Royal Opera House until 31 March.